Greysheet & CPG® PRICE GUIDE

- U.S. Coins /

- Pattern Coinage /

-

Patterns (1942) Values

Year

Sort by

About This Series

History and Overview

In the summer of 1941, America was the “arsenal of democracy,” providing munitions, aircraft, ships, and other supplies to nations in Europe and Asia overrun by the Nazis and the Japanese. Copper and nickel, both strategic metals, were in tight supply, and the Treasury Department made plans to alter the alloys used in coinage, and use substitutes. Eventually, this translated into the silver-content “wartime” five-cent pieces made from 1942 to 1945 and the zinc-coated steel Lincoln cent made in 1943.

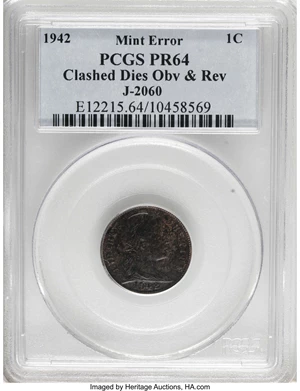

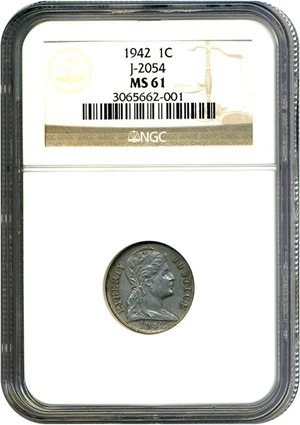

In 1942, by which time the United States was directly involved in World War II, several manufacturers were contacted and asked to perform experiments on substances that could be used in place of copper for the Lincoln cent.12 Among the eight plastics firms and one glass company involved were the Hooker Chemical Co. and Durez Plastics and Chemicals, Inc., both of North Tonawanda, New York; the Colt Patent Firearms Co. in Hartford, Connecticut; and Tennessee Eastman Corporation. Not wanting to release official coinage dies for testing, Chief Engraver John R. Sinnock created cent-sized dies with a female portrait on the obverse (as used on the Colombian two-centavo coin, but with the lettering LIBERTY / JUSTICE to the left and the right). The reverse motif was an open wreath enclosing UNITED STATES MINT.13

Three of the plastics firms were each provided with a sample pattern, struck in bronze, to compare with their own experimental results. The companies were invited to explore various materials, including red fiber, plastic of various colors, hard rubber, Bakelite, tempered glass, zinc, aluminum, white metal, manganese, and thinner forms of bronze planchets. Many such pieces were made, but it seems that no precise record of them has ever been found.

In addition, regular 1942 Lincoln cent dies are said to have been used to strike coins in pure zinc, copper and zinc, zinc-coated steel, aluminum, copperweld, antimony, white metal, and lead, among other materials.

Collecting Perspective

In the 7th edition of this text, Dr. Judd noted, “The legal status of these experimental pieces remains in doubt. One piece was seized while another offering at auction was not disturbed. Perhaps one day a clear policy will be defined. As it is whenever any change in coinage is contemplated, a hazy situation develops surrounded by secrecy and misinformation.” The listings below represent materials known to have been used for these experimental pieces, or mentioned in numismatic or other literature. Not all may exist. The numbering is open-ended, reserved for future use if other materials are discovered.

Catalog Detail

Legal Disclaimer

The prices listed in our database are intended to be used as an indication only. Users are strongly encouraged to seek multiple sources of pricing before making a final determination of value. CDN Publishing is not responsible for typographical or database-related errors. Your use of this site indicates full acceptance of these terms.

From the Greysheet Marketplace

Buy Now: $3,695.00

Buy Now: $2,890.63

Buy Now: $120,000.00

Buy Now: $38,900.00

Buy Now: $5,500.00

Buy Now: $37,000.00

Buy Now: $3,121.88

Buy Now: $37,000.00

Buy Now: $31,500.00

Buy Now: $125,000.00

Related Stories (powered by Greysheet News)

View all news

Greysheet Catalog Details

History and Overview

In the summer of 1941, America was the “arsenal of democracy,” providing munitions, aircraft, ships, and other supplies to nations in Europe and Asia overrun by the Nazis and the Japanese. Copper and nickel, both strategic metals, were in tight supply, and the Treasury Department made plans to alter the alloys used in coinage, and use substitutes. Eventually, this translated into the silver-content “wartime” five-cent pieces made from 1942 to 1945 and the zinc-coated steel Lincoln cent made in 1943.

In 1942, by which time the United States was directly involved in World War II, several manufacturers were contacted and asked to perform experiments on substances that could be used in place of copper for the Lincoln cent.12 Among the eight plastics firms and one glass company involved were the Hooker Chemical Co. and Durez Plastics and Chemicals, Inc., both of North Tonawanda, New York; the Colt Patent Firearms Co. in Hartford, Connecticut; and Tennessee Eastman Corporation. Not wanting to release official coinage dies for testing, Chief Engraver John R. Sinnock created cent-sized dies with a female portrait on the obverse (as used on the Colombian two-centavo coin, but with the lettering LIBERTY / JUSTICE to the left and the right). The reverse motif was an open wreath enclosing UNITED STATES MINT.13

Three of the plastics firms were each provided with a sample pattern, struck in bronze, to compare with their own experimental results. The companies were invited to explore various materials, including red fiber, plastic of various colors, hard rubber, Bakelite, tempered glass, zinc, aluminum, white metal, manganese, and thinner forms of bronze planchets. Many such pieces were made, but it seems that no precise record of them has ever been found.

In addition, regular 1942 Lincoln cent dies are said to have been used to strike coins in pure zinc, copper and zinc, zinc-coated steel, aluminum, copperweld, antimony, white metal, and lead, among other materials.

Collecting Perspective

In the 7th edition of this text, Dr. Judd noted, “The legal status of these experimental pieces remains in doubt. One piece was seized while another offering at auction was not disturbed. Perhaps one day a clear policy will be defined. As it is whenever any change in coinage is contemplated, a hazy situation develops surrounded by secrecy and misinformation.” The listings below represent materials known to have been used for these experimental pieces, or mentioned in numismatic or other literature. Not all may exist. The numbering is open-ended, reserved for future use if other materials are discovered.

Catalog Detail

Legal Disclaimer

The prices listed in our database are intended to be used as an indication only. Users are strongly encouraged to seek multiple sources of pricing before making a final determination of value. CDN Publishing is not responsible for typographical or database-related errors. Your use of this site indicates full acceptance of these terms.

Loading more ...

Loading more ...