A Brief History Of James B. Longacre's One Dollar Gold Coins, Part 1

An overview of how the gold dollar originated and evolved in the mid-1800s.

The Coinage Act of 1792 established a minting facility at the seat of Government (Philadelphia, at that time), several of its major functions, and a number of its officers and duties. It also decreed the number of different denominations of coins that should be struck, from the Gold Eagle ($10) coin, down to the Half Cent, struck in copper.

A dollar coin was also provided for, but it was to be struck out of “four hundred and sixteen grains of pure silver.” The original intent was for the fledgling United States not to have a gold one-dollar coin. These decisions were approved by Congress and by President George Washington. The silver dollar of 1794 to 1803 competed well with the Spanish Milled Dollar of the era in the worlds’ marketplaces. However, its minting was suspended in 1803, since the majority of these coins were being exported.

When gold was discovered in the 1820s and 1830s in Georgia and in North Carolina it led to a goldrush and the U.S. Mint and the Treasury were convinced to establish branch mint locations in Dahlonega, Georgia and in Charlotte, North Carolina in 1835. However, while gold was abundant in both sites, each of the branch mints primarily struck $2.50 and $5.00 gold coins. Additionally, the Dahlonega mint struck a $3.00 gold coin, but only in 1854. No denominations larger than $5.00 were struck at either mint.

However, when gold was discovered in California, it was a different matter entirely. The amount of gold taken from various areas of California far exceeded the amount discovered in North Carolina and Georgia. The U.S. Mint created plans to establish another branch mint, this time in San Francisco.

Now with the quantities of gold exceeding expectations, a small gold coin and a large gold coin were needed to transact commerce, especially in California. The Act of March 3, 1849 created both a small $1.00 gold coin as well as a large $20.00 Double Eagle gold coin. The bill passed both Houses of Congress, with amendments, and was signed into law by President Polk in 1849.

Now with a Gold Dollar to be struck, the Mint and the Secretary of the Treasury needed new coinage designs. They turned to James B. Longacre, the Chief Engraver of the Mint, who served from 1844 until 1869. Longacre, who was the Chief Engraver since the death of Christian Gobrecht, was not a well-respected artist by Mint officials. Since he knew he would not have a great deal of time to create a design, Longacre worked on it incessantly. Meanwhile some Mint officials discussed having an outside artist create the design.

Longacre had written of his difficulties in creating the dies for this exceptional small coin, “The engraving was unusually minute and required very close and incessant labor for several weeks. I made the original dies and hubs for making the working dies twice over, to secure their perfect adaptation to the coining machinery. I had a wish to execute this work single handed, that I might thus silently reply to those who had questioned my ability for the work. The result, I believe, was satisfactory,” said Longacre.

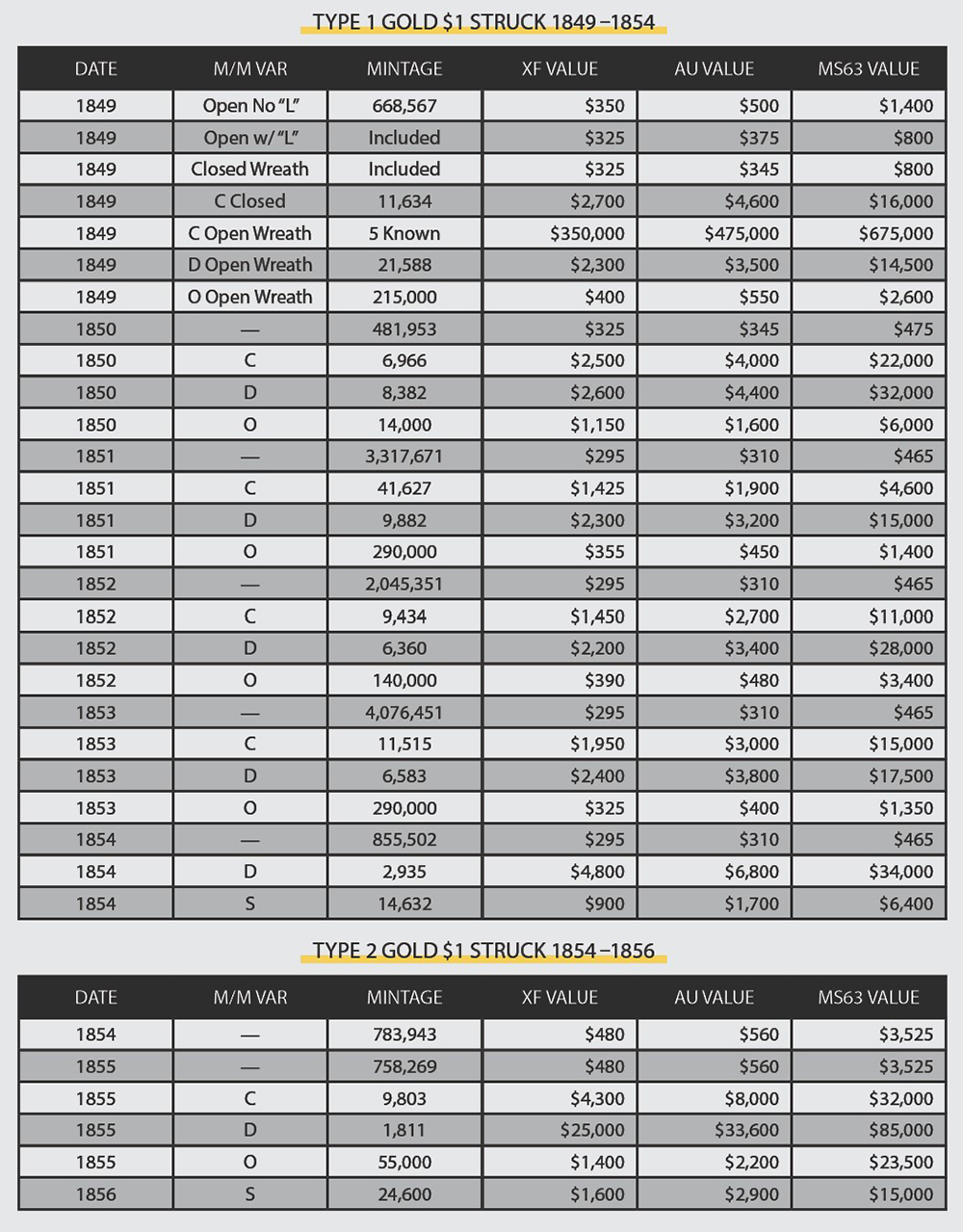

Longacre’s coin depicted an allegorical representation of Miss Liberty, facing to the left. She is surrounded by 13 six-pointed stars. Longacre included his initial "L" on the truncation of Liberty's neck. That “L” was the first time an American coin that was intended for circulation bore the initial of its designer. Some of the 1849-dated coins struck at the Philadelphia Mint have the designer’s “L” and some do not.

The reverse depicts a wreath which is open at the top. Inside the wreath is a numeral “1” and beneath that is the word “DOLLAR. The date of minting is below that, yet it is still inside of the wreath. Around the reverse periphery is “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.”

The coin achieved some favorable acclaim from contemporary media. The New York Tribune described the new dollar as “undoubtedly the neatest, tiniest, lightest, coin in this country… it is too delicate and beautiful to pay out for potatoes, and sauerkraut, and salt pork.”

But other comments were not quite so positive, one drawing upon the most common complaint about the coin—its size, “there is no probability of them ever getting into general circulation; they are altogether too small.”

During the initial year, 1849, coins were struck in Philadelphia, Charlotte, Dahlonega, and New Orleans, and during that year there were two major varieties—an “Open Wreath” and a “Closed Wreath.”

The Open Wreath variety has leaves on the left side of the coin in line with the first “T” in “STATES,” while the right side of the coin has leaves in line with the first “A” in “AMERICA.”

The Closed Wreath on the other hand has the end of the leaves on the left side in alignment with the “A” in the word “STATES,” and the right side leaves align with the “O” in the word “OF.”

This first design of Gold Dollar coin was struck from 1849 through 1854 but beyond the “Open Wreath” and “Closed Wreath,” no major varieties exist in the series.

As gold continued to be mined in California, the availability of gold increased while the value of silver increased. It therefore became profitable to export U.S. silver coins out of the country to be melted. This meant that now the Gold Dollar, the one cent piece, and the $2.50 gold Quarter Eagle became the most available coins in circulation.

But the coin was only 12.7 mm in diameter, making it the smallest and lightest coin ever made by the United States Mint. Even the silver Three Cent Pieces of 1851 to 1873 are larger at 14mm. That size, commensurate with the current price of gold, would continue to prove to be problematic.

While the Type 1 design was well executed, the coin was simply too small for comfort. A dollar, in the 1850s, could typically represent a day’s wages, so losing that coin would be devastating. Due to numerous complaints from all circles, changes were coming to the one dollar gold coin. In 1853, James Ross Snowden became the new Director of the Mint. Snowden heard the many complaints about the coin’s size, so he directed Longacre to redesign the Gold Dollar.

All agreed that the coin was too small, and Snowden wanted it larger. However, he wanted it larger without adding more weight to the coin or adding a hole to it. So the coin would have to be made thinner, in order to be made larger. The diameter was increased by 15% by making the coin thinner.

The new head of Miss Liberty has been commonly described as an ‘Indian Princess,’ however it is believed that Longacre was influenced by a Roman marble figure. He may have seen the statue of Lely’s Crouching Venus, as it was being displayed at a Philadelphia Museum around the time of the redesign.

SOLD FOR $528,750.00 January 2016 by Heritage auctions.

Longacre’s new design removed the stars from the periphery on the obverse. The stars were replaced with the inscription “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.” Miss Liberty still faced to the left, except that her face and head were larger, and she wore an Indian-style headdress.

The reverse had a much larger and more ornate agricultural wreath. It depicted corn, cotton, tobacco, and wheat—but it still retained the numeral “1,” the word “DOLLAR,” and the date inside the wreath. The new wreath also had a larger and more ornate bow, Thinking that he solved the one dollar gold coin’s problems by increasing the diameter, Longacre unknowingly created new problems.

The design, especially on the obverse, was much higher in relief than the previous design. Now when the reverse side was struck, the wreath and the date and denomination were hard to see. The new size made for a bigger coin, however the higher relief made for uneven or poor strikes. Often times, the date or the denomination were incomplete. So a bad situation was now made even worse by the intended enhancements.

SOLD FOR $373,750.00 January 2008 BY Heritage auctions.

The Mint started out cautiously and struck these new Type Two coins in smaller mintage numbers and due to these new problems, they were struck only between 1854 and 1856.

It wasn’t only the Philadelphia Mint that had issues striking these new designs. The quality of the coins coming from the three Southern branch mints—Charlotte, Dahlonega, and New Orleans—had even more issues with striking this new design. Many of the branch mints’ examples were sent back to Philadelphia for melting and restriking.

In their initial year, 1854, the only coins struck were minted at the Philadelphia facility. During 1855, coins were struck at Philadelphia, Charlotte, Dahlonega, and New Orleans. The branch mints struck coins but in much lower numbers than were being struck at the main mint in Philadelphia. By 1856, the final year for this issue, coins were only struck at the San Francisco Mint, again in very low numbers.

Numismatic art historian, Cornelius Vermeule was definitely not impressed with Longacre’s efforts for this Type Two coin. In his book, ‘Numismatic Art in America: Aesthetics of the United States Coinage,’ Vermeule stated, “the princess of the gold coins was a banknote engraver’s elegant version of the folk art of the 1850s. The plumes or feathers are more like the crest of the Prince of Wales than anything that saw the Western frontiers, save, perhaps, on a music hall beauty.”

Neither contemporary comments, nor those like Vermeule’s written in the 21st century, were kind to Longacre’s second version.

Would there be a third design? Part Two—Coming Soon

Images courtesy of Heritage Auctions & Wikimedia.

Download the Greysheet app for access to pricing, news, events and your subscriptions.

Subscribe Now.

Subscribe to The Greysheet for the industry's most respected pricing and to read more articles just like this.

Author: Michael Garofalo

Please sign in or register to leave a comment.

Your identity will be restricted to first name/last initial, or a user ID you create.

Comment

Comments